Down With Algorithms, or Why Curators Rule

Algorithms now seem to dictate life, perhaps more so than ever before. They power Google searches, Facebook feeds and Netflix recommendations, facilitate stock trades, influence which movies get made and write news stories. Apps like Vango have turned searching for and purchasing art into an algorithm: you upload a photo of your space and based on the colors in it, the app supplies “personalized” art recommendations.

As defined by Meriam-Webster, an algorithm is “a step-by-step procedure for solving a problem or accomplishing some end.” At its most basic, then, an algorithm is a decision-making process. Seen in this light, we arguably could all be walking talking algorithms as we drive to work, execute flow charts, cook dinner and fold laundry.

Best-selling author Steve Almond, in his book This Will Only Take a Minute Honey, boils writing down to “decision making. Nothing more and nothing less.” All art, in essence, is a manifestation of the decisions its creator made: where to leave the canvas blank, when to hit E-flat, where to place a semi-colon, when to leap, when to exit stage right. But, as any artist will tell you no matter her medium, no step-by-step procedure for creating art exists; the road zig-zags, winds in circles, dead-ends and detours before finally reaching its destination.

Something as elusive and hard-won as art should be treated with the same care, thought and respect that went into its creation. Which is why algorithms, when it comes to curating, should not touch art, even with a ten-mile long code. I’m not saying algorithms are careless, thoughtless or respect-less – of course not – it takes very skilled, intelligent, upstanding people to craft them. But art deserves better than a code however thoughtful it may be (Dewey Decimal Classification notwithstanding.) Great art and a great art collection demand a great curator, someone who can make unexpected associations between seemingly disparate pieces, provide a new avenue into and out of each piece and a collection as a whole, unearth new meaning and create new context.

Let’s look at my unscientific case study: Pandora vs. OpenAir. Pandora, more than any other sound, reverberates through the Nine dot Arts office for eight-plus hours a day, five days a week. You could say we’re a bit co-dependent. I can’t speak for the rest of the Dots, but when it’s quiet, I’m extremely self-conscious of the speed (or lack thereof) of my keyboard and mouse clicks, the loudness my throat clearings and nose blowings. Inevitably, I will ask someone to play music within ten minutes of it stopping.

As much as I love the cloak of audio invisibility Pandora provides, I kind of hate it, too. While each song is different, they all share a certain monotony in beat, melody, chord progression, etc. Listen to the same station long enough and frequently enough, and you’re going to hear the same songs over and over again. You could argue that most radio stations do the same; locked into a particular genre, there is a finite number of songs and artists available, making repetition inevitable. Rarely, do I “discover” a new band or artist on a Pandora station. When I click on Decemberists Radio, I know exactly what I’m going to get. While such certainty can at times be comforting, it is not exciting or stimulating. Even if I love an individual song, more often than not when I’ve heard it on Pandora, it just feels like oatmeal in my ears.

Now, let’s examine OpenAir, Colorado Public Radio’s new music station with a Colorado perspective. How exactly does OpenAir define “new” music? As open as the air itself: Woody Guthrie to the Beach Boys to Kishi Bashi to Paper Bird to Wheelchair Sports Camp. I rarely hear the same song twice in a day let alone in a week. The truly staggering depth and breadth of their library grows daily. What I love about OpenAir is that it’s curated by knowledgeable, passionate people who have slogged through all the noise for me. Do I love every song? No. In fact, some songs I have despised so much, I’ve muted the sound or changed the station entirely. As Forrest Gump says, “You never know what you’re gonna get.” Each song, each hour is continually surprising which makes it utterly, un-ignorably, tantalizingly engaging. Algorithms like Pandora’s, however, deal in similarities. (If you like song X, then you’ll like song Y because they share fifteen points of commonality.) This kind of insistent likeness breeds a solid “meh.” It’s like putting art on a steady diet of Prozac and cold, bland porridge.

At Nine dot Arts, you could say we are curators in consultants’ clothes. We look for magic in each and every piece we place. Whether it’s to create surprises around every corner in a law firm, reenergize a convention corridor, take a hotel guest’s breath away or provide a hospital patient a moment of respite, we aim to transform a stale environment into an unforgettable experience. Our mission in life is to get you to spend your fifteen-minute break visiting your favorite painting or make you change routes to the water cooler just so you can avoid that photograph you disdain – to turn “meh” into “me likey!” or “me no likey,” as the case may be. That type of engagement is curatorial gold. It breaks through our super-saturated, information-inundated world, jars us out of the mundane and reminds us what it’s really like to be present and, ultimately, what it’s like to be alive. Damn right: curators rule!

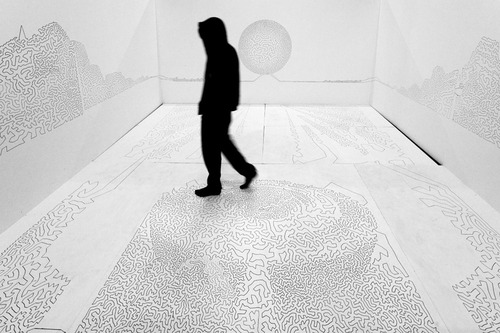

Photo information:

Towards the end of 2012, as part of The Festival of the Mind in Sheffield, Mattias Jones and a small team of technicians, coders and mathematicians developed a drawing system derived from theories on how bees fly from flower to flower. It ended up covering three walls and the floor of a twenty foot cube in one unbroken line. Photography by Andy Brown.